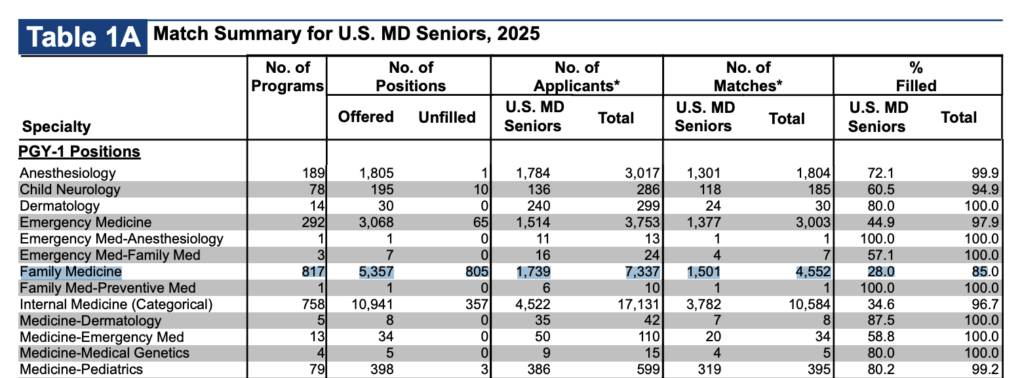

Another year of the NRMP match results, and Family Medicine continues to be a relentless slow-moving disaster within the house of medicine. 805 unfilled postions, only 28% filled by US MDs. Just 1,501 US MDs in the whole country matched to one of the most critical jobs in all of healthcare (1739 applied, but the discrepency is probably a reflection of FM being a back up option for several hundred people).

I think people see this and point out several obvious deficiencies:

- Pay

- Prestige/respect

- Midlevels

All true. All essentially impossible to easily fix within medicine and our training paradigms. Some people discuss the possiblity of special loan reimbursement, and that I suppose is obliquely helpful, but the reality is that PSLF already exists and there are already programs for working in underserved areas. Debt is a problem, but I don’t think tackling that head-on is going to solve the decline of primary care in the US.

Another suggested solution I often hear is to make family medicine sexier by allowing for different fellowships, creating more training options and allowing family docs to broaden their skills into things like dermatology.

There may be something to this, though I suspect in most cases, there probably isn’t. Even if such broadening were successful, it is probably counterproductive to the actual goals of primary care. A backdoor into dermatology is probably not going to solve a shortage of qualified practitioners. Nor do I think additional training is going to improve perceptions of prestige or respect.

The thing the ACGME can do to make things better are to change the training composition/requirements and especially length. Family Medicine should probably be a shorter, outpatient-focused course of training for general practitioners in the US.

In the era of massive midlevel expansion, it simply can’t be three years long. Anything else isn’t going to work.

In a world where many institutions struggle to attract aspiring family practitioners, I suspect the only solution is to fight fire with fire. I think we need more efficient training. We need to acknowledge that while more training is always good, it isn’t always necessary. And if we can’t get the job done in less time, then we need to seriously consider the efficiency of our process and the ability of our tools to assess competence.

We have, for too long, resorted to a proxy metric of time to tell us that somebody is skilled. This crude tool shouldn’t be the best we can hope for going forward. Nor will it help us address a possible post-AI world where physician retraining may become a more pressing concern.

So, I think the answer is just to start by shaving off a year and getting it done in two years. I honestly wonder if one could really focus even more on outpatient medicine and do it in a year, but I suspect not only would that be a logistical problem, it would also cause major disruptions, given the scale of change. That said, strict training lengths are important to hospitals using residents for predictable labor. The ebb and flow of patients in a resident clinic is probably slightly easier to accommodate.

Given the current reality that many people in family medicine do not want to practice a significant amount of inpatient medicine, refocusing a portion of that to an optional third year instead of making it a core part of the residency is likely one way to offer flexibility without fundamentally changing the field. Offering different paths for those who want to work in rural areas doing procedures and those who want to do OB are great ideas, but some serious introspection to figure out what the core of a PCP/GP should be in the US is overdue.

I also want to preempt anyone who thinks that doctors are already poorly trained and that shortening training will worsen that problem. Many older physicians indeed believe that younger physicians are graduating “less well-trained” than previous generations. Part of that is a manifestation of reduced training volume. Part of it may be related to the increasing complexity of medicine. And part of it may be related to cultural shifts, such as decreased studying after work and other such factors. But the baseless assumption here is that there is no fat to trim, that all months of training are essentially equally useful, and that a shorter process should look the same as the longer process, just worse.

The reality is that we cannot afford to ignore training quality. We can provide better, more effective training. We need better measures. We need to reward hard work and variable skill so that the most competent people can graduate when they’re ready and not just when they’re older.

And ultimately, we need to rethink our fixation on time as the defining measure of competency. It’s not. It’s a crutch.

6 thoughts on “Family Medicine Needs a Rethinking”

This is really concerning—especially given how essential Family Medicine is to the entire healthcare system. The numbers make it clear there’s a deeper structural issue that needs attention. Discussions like this matter, much like how communities (even ones like eaglercraft) surface problems early so they don’t get ignored.

Just unlocked a crazy sound in Sprunki Game that I never expected. Can’t wait to experiment more!

One issue to shortening FM training to ‘compete with midlevel’s'[my interpretation] is that the adjudication of medical errors still punishes the doctoral provider {MD DO} at a more harsh level than the midlevel.

Training for ‘rural practice’ options is offered as a track in some medical schools. I believe that this has not encouraged rural practice as a choice in the Midwest and Southwest. Even though I was so trained back in the day, I have to say I did not remain in a rural area.

Although I value all the skills I learns, I never use them now as I’m not allowed to. Funny, I can oversee a PA FNP doing those procedures that do them, even if I can no longer do them [Dermatology in particular].

I totally agree. Decreasing training to two years would be a fatal mistake. I did research years ago about increasing family medicine to a four year residency! We solve this problem by paying us more, decreasing administrative responsibilities, and accepting the right people into medical school. Also require medical schools to graduate 10% of their class into family medicine or lose federal funding.

This will be my 30 + year of practice in rural medicine. I am so very thankful of the training I got over the 3 years of my family medicine residency! It’s my opinion that we, as family physicians , are a vital part of patient care. Don’t cut our training down,

that’s what separates us from mid levels .

There is nothing better than knowledge , skill, and experience!! There isn’t a day that I don’t feel respect and gratitude from the patients I see !! Don’t settle !!! Have expectations, and still , in family medicine you can make a difference……..

I totally agree! Don’t cut down our training. It’s what makes us excellent problem solvers and separates us from mid levels. Decrease our administrative burden and offer loan repayment for all going into Family Medicine to entice more residents. I love being a Family Physician.