If you’re pulling in a physician’s salary, you’ve likely hit the income ceiling that locks you out of contributing directly to a Roth IRA.

This is just one of those “first-world problems” that troubles those of us who like to do things (like building wealth) efficiently. The “problem” here is the privilege of choice.

In the world of high earners, you’ve got options, and understanding the nuances between backdoor Roth conversions and taxable investing could mean the difference between leaving money on the table and optimizing your tax strategy for decades to come.

So, what actually makes sense for physicians and other high earners in 2026? Let’s get down to brass tacks.

In case you missed it: Physician Compensation 2025: Modest Gains and Deeper Financial Pressures

Understanding the Backdoor Roth

The backdoor Roth IRA isn’t some shady tax loophole. It’s a perfectly legal strategy that Congress has essentially blessed us with by not shutting it down despite multiple opportunities to do so. Here’s how it works:

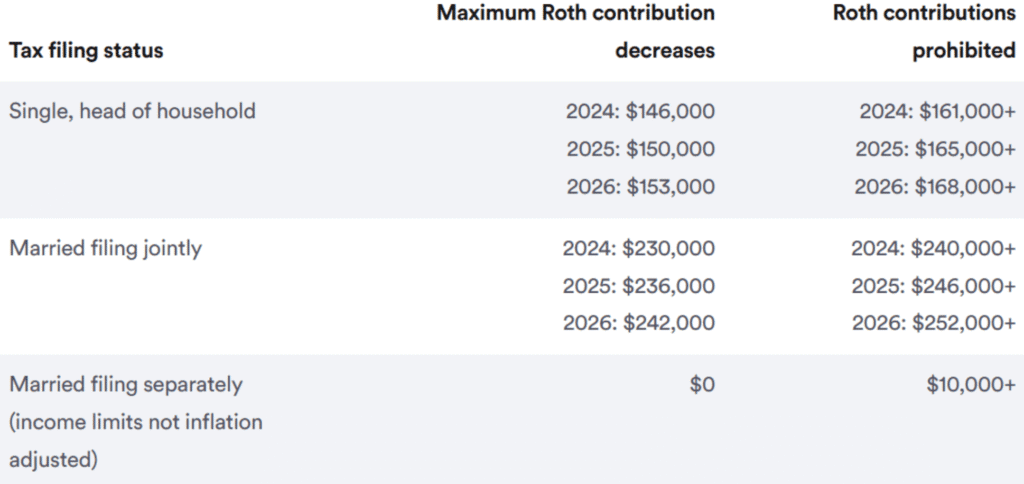

For 2026, if you’re a single filer making more than $168,000 or a married couple filing jointly earning over $252,000, you can’t contribute directly to a Roth IRA.

The phase-out actually starts at $153,000 for singles and $242,000 for married couples.

For most attending physicians, these thresholds are in the rearview mirror.

Source: Bankrate

Luckily, there’s a workaround. You make a non-deductible contribution to a traditional IRA (anyone with earned income can do this, regardless of how much they make), then immediately (or pretty darn close to immediately) convert those funds to a Roth IRA and just like that, you’re in.

CPA and nationally recognized retirement expert, Ed Slott calls Roth IRAs “the gold standard.” And the backdoor route is how high earners access that gold standard.

The contribution limit for 2026 is $7,500 if you’re under 50, or $8,600 if you’re 50 or older. Not a king’s ransom by any means, but it’s a tax-advantaged space you’d otherwise be locked out of.

The Mechanics

The process is straightforward, though you’ll want to dot your i’s and cross your t’s:

- Open a traditional IRA (if you don’t already have one)

- Make a non-deductible contribution of up to $7,500 (or $8,600 if you’re 50+)

- Wait a hot second. Slott recommends about a month to ensure your IRA statement reflects the contribution

- Convert to Roth. You’ll initiate the conversion through your brokerage

- File Form 8606 with your taxes to document the non-deductible contribution

Most major brokerages (Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab) make this process relatively painless with online tools specifically designed for conversions.

A Gotcha You Need to Know About

Here’s where things can get messy. If you have any pre-tax money sitting in traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, or SIMPLE IRAs, the IRS uses the pro rata rule to determine how much of your conversion is taxable.

Let’s say you’ve got $93,000 in a traditional IRA from an old 401(k) rollover, and you contribute $7,500 for a backdoor Roth. The IRS doesn’t let you cherry-pick which dollars you convert.

Instead, they look at your total IRA balance across all accounts. In this scenario, you’d owe taxes on roughly 93% of your $7,500 conversion. That defeats the whole purpose.

The workaround? Roll those pre-tax IRA dollars into your current employer’s 401(k) (if they allow it) before doing the backdoor conversion. Most 401(k) plans accept incoming rollovers, but you’ll need to check with your plan administrator.

The Backdoor Roth Advantage

The beauty of the backdoor Roth is what happens after the conversion. That $7,500 (or $8,600) grows completely tax-free for as long as you want. No required minimum distributions (RMDs) during your lifetime. No taxes when you withdraw in retirement.

Unlike traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs don’t have RMDs, making them exceptional estate planning vehicles.

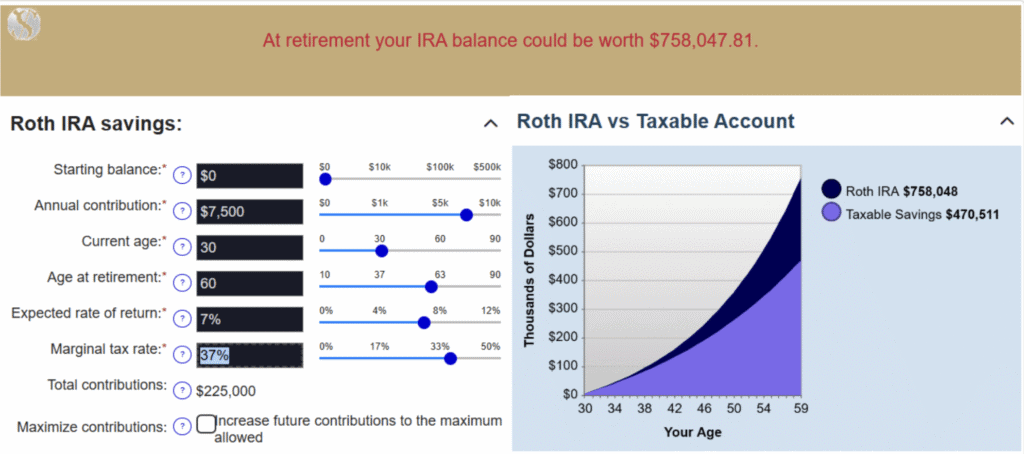

According to this calculator, over 30 years, that annual $7,500 contribution (assuming a 7% average return) could grow to roughly $758,048 — and you won’t owe the taxman a dime when you take it out.

“You’re going to pay the upfront income tax anyway, but the backdoor Roth IRA ensures that the earnings are tax-free. There’s nothing but upside to do a backdoor Roth IRA,” notes one user on Reddit.

Backdoor Roth IRA 2025: A Step-by-Step Guide with Vanguard

The Downsides

Of course, nothing in this world can be perfect, and the backdoor Roth has its limitations.

- Limited contribution space: $7,500 annually isn’t going to fund your entire retirement, especially if you’re starting later in your career.

- Administrative hassle: You’ll need to file Form 8606 every single year you do this. Miss it, and you could end up paying taxes twice on the same money.

- The five-year rule: To withdraw earnings tax-free, you need to have had a Roth IRA open for at least five years and be 59½ or older.

- Legislative risk: While unlikely, Congress could close the backdoor. The Build Back Better proposal in 2021 attempted this (though it failed). It’s a political football that could get punted again.

- Conversion timing: If your contribution gains value before you convert, you’ll owe taxes on that growth. This is why most people convert within days of contributing.

Taxable Investing: The Underrated Workhorse

On the other hand, we have the regular old taxable brokerage account. The one that doesn’t get much love in retirement planning circles but might actually deserve more respect than it gets, especially for high earners with long-term goals.

A taxable brokerage account is exactly what it sounds like. It’s an investment account where you buy stocks, bonds, ETFs, mutual funds, or other securities using money you’ve already paid taxes on. You can invest as much as you want, whenever you want. No contribution limits. No age restrictions. No withdrawal penalties.

The catch? You’ll pay taxes along the way — on dividends, on interest, and on capital gains when you sell. But…those taxes aren’t necessarily the wealth-killer that conventional wisdom makes them out to be.

How Taxable Accounts Are Taxed

The tax treatment of taxable accounts is actually more favorable than most people realize:

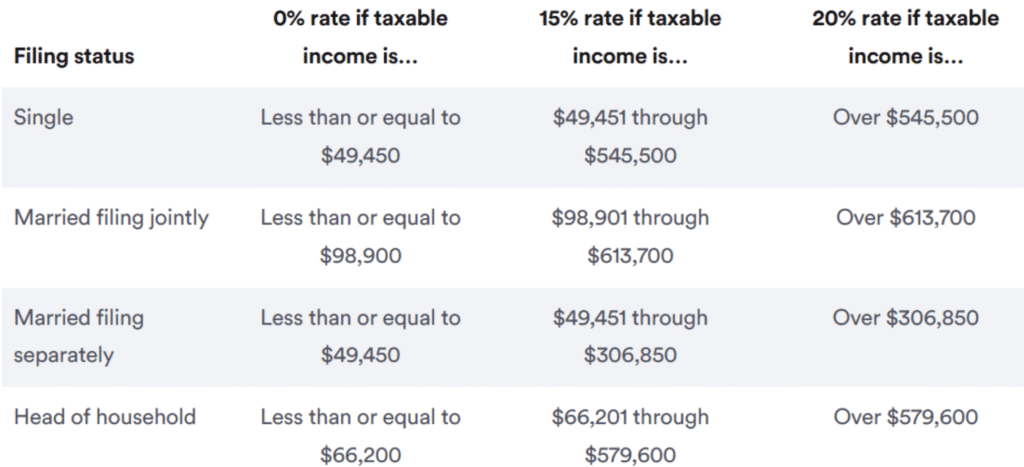

Qualified dividends and long-term capital gains (assets held more than one year) are taxed at preferential rates: 0%,15%, or 20%, depending on your taxable income.

For 2026, single filers don’t hit the 20% rate until taxable income exceeds $545,500, and married couples filing jointly don’t hit it until $613,700.

Short-term capital gains (assets held one year or less) are taxed as ordinary income at your marginal rate, which for high-earning physicians could be as high as 37% federal plus state taxes.

This is why buy-and-hold strategies make sense in taxable accounts.

Whereas, ordinary dividends get hit at ordinary income rates, but if you’re investing in tax-efficient index funds like VTI or VTSAX, most of your dividends should qualify for preferential treatment.

One often-overlooked advantage is that you only pay capital gains taxes when you actually sell. That money can compound for decades without any tax drag on the unrealized gains. As long as you’re holding, you’re not paying taxes on growth — just on the dividends kicked off along the way.

Source: Bankrate

Now Make It Tax-Efficient

Not all investments are created equal in taxable accounts, and here’s what the smart money does.

Stick with tax-efficient core holdings like broad-market index funds such as VTI, VTSAX, or FZROX, which are the bread and butter of taxable investing since these funds have minimal turnover (meaning they don’t trigger capital gains distributions often) and most of their distributions are qualified dividends.

Meanwhile, actively managed funds with high turnover, REITs, taxable bonds, and high-dividend stocks are generally better suited for tax-advantaged accounts, since, as one analysis notes, “investments that generate high levels of income or capital gains distributions for investors are often better to be held in tax-advantaged accounts.”

However, where taxable accounts truly excel is in tax-loss harvesting.

This lets you sell investments when they drop in value to realize losses, then immediately buy something similar (but not identical to avoid the wash sale rule), using those losses to offset gains elsewhere in your portfolio while deducting up to $3,000 in excess losses against ordinary income annually and carrying forward unused losses indefinitely.

Why Taxable Accounts Punch Above Their Weight

Here’s what you can do with a taxable account that you can’t do with retirement accounts:

- Access your money anytime: No 10% early withdrawal penalty. No hoops to jump through. If you want to buy a house, start a business, or retire at 50, your money is there.

- No required minimum distributions: Unlike traditional IRAs and 401(k)s, taxable accounts don’t force you to take RMDs starting at age 73 (as of 2026). You control when and how much you withdraw.

- Step-up in basis: When you die, your heirs get a step-up in cost basis to the fair market value at your death. Translation: all those unrealized capital gains? Gone. Your heirs can sell immediately and owe zero capital gains tax. This makes taxable accounts phenomenal wealth transfer vehicles.

- Charitable giving: You can donate appreciated securities directly to charity, avoiding capital gains taxes entirely while getting a charitable deduction for the full market value. This is one of the most tax-efficient charitable giving strategies available.

Also read: Pray for Beta, Not Alpha

Going Head-to-Head: Backdoor Roth vs Taxable for Physicians

So if you’re a physician making $300,000+ annually, you’re likely already maxing your 401(k).

($24,500 in 2026, or $32,500 if you’re 50+) (As an aside, if you’re a high earner making over $150,000 in 2025 wages, just know that starting in 2026, your catch-up contributions have to go into a Roth account. You’ll pay taxes on them now instead of later, though the upside is tax-free withdrawals down the road.)

You might also have access to a mega backdoor Roth through your employer (if you’re lucky enough to have after-tax 401(k) contributions available). But you’ve still got money left over each month. What do you do?

The Case for Doing Both

You can cut out the dilemma altogether. This doesn’t have to be an either/or situation. If you’ve got the cash flow, you should be doing the backdoor Roth and investing in a taxable account.

Maximum Optionality

“I currently max out my 401k, so my options for further investing are brokerage, regular IRA, and backdoor Roth. Of these options, all will use after tax money, but the Roth IRA is the only one that won’t tax capital gains, so it is definitely worth it to me,” explains one high-income earner on Reddit who does exactly this approach.

The backdoor Roth gives you $7,500–$8,600 of guaranteed tax-free growth annually. That’s a no-brainer. But once you’ve maxed that out, every additional dollar is going into either a traditional IRA (which makes no sense without a deduction) or a taxable account.

The taxable account wins that toss-up every time.

Asset Allocation

Building wealth can sometimes be like playing a board game. Not Monopoly, no. Not checkers either. I’m talking about chess.

The smartest play is putting high-growth assets like stocks, especially higher-volatility positions that could see outsized returns in your Roth accounts, where if a stock 10x’s, all that growth is tax-free forever.

“All high wage earners should consider looking at both a backdoor Roth IRA and a mega backdoor Roth IRA if they can’t set up a Roth IRA,” notes financial advisor Ted Jenkin, CFP® and member of the CNBC Financial Advisor Council.

Meanwhile, broad market index funds with low turnover and qualified dividends work beautifully in taxable accounts, where you’ll pay some taxes on dividends annually (typically 15% for most high earners) but long-term capital gains remain taxed favorably.

Save your tax-inefficient assets (bonds, REITs, and other high-income investments that get hammered in taxable accounts) for your 401(k) or traditional IRA, where they belong in tax-deferred space.

The “Expected Tax Bracket in Retirement” Debate

Conventional wisdom says that if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket in retirement, prioritize traditional/pre-tax accounts. If you expect to be in a higher bracket, go Roth.

But there’s that wisdom often misses for physicians. You might be in a lower marginal bracket in retirement, but you could still face substantial tax bills due to RMDs, Social Security taxation, and other income sources.

It’s more a question of your marginal tax rate now vs. your average tax rate in retirement. If you’re in the 35% or 37% federal bracket now, even with a “lower” retirement bracket of 24% or 28%, you’re still paying a hefty chunk.

The backdoor Roth hedges this uncertainty. You’re paying taxes at today’s known rates (on the contribution, not the conversion, since it’s non-deductible) and locking in tax-free treatment forever.

Early Retirement Considerations

If you’re eyeing FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) or planning to hang up your stethoscope before 59½, taxable accounts become even more valuable.

Why? Access. While you can tap Roth IRA contributions (not earnings) anytime penalty-free, and there are workarounds like 72(t) substantially equal periodic payments or a Roth conversion ladder, taxable accounts just… work. No paperwork. No five-year waiting periods. No penalties.

“The key to my brokerage accounts is just that I will not be working until 59.5 so I am accumulating in VTSAX and FZILX,” writes one Bogleheads member planning to retire at 50.

The Marriage Penalty and NIIT

High-earning married couples face two additional tax considerations that can sting.

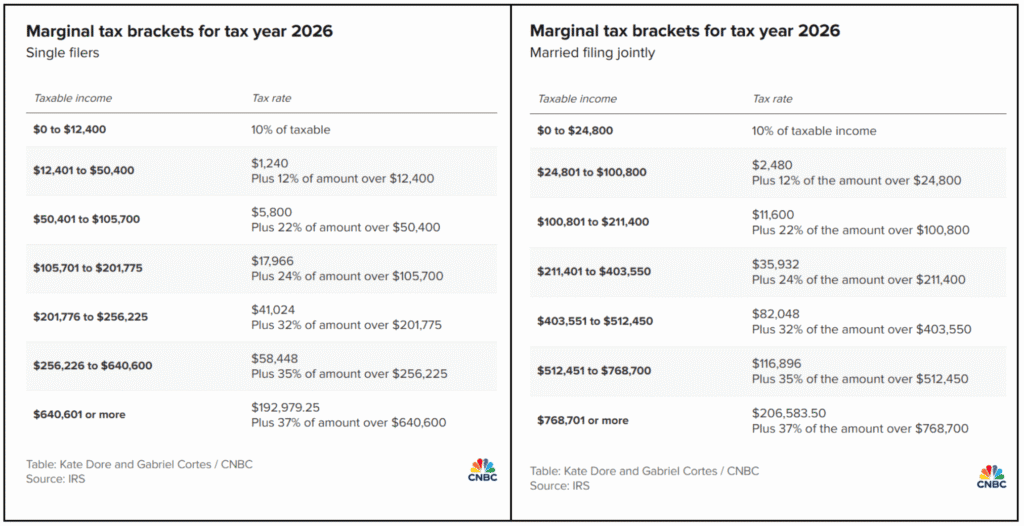

First, there’s the marriage penalty. Tax brackets for married couples aren’t exactly double those for singles, so for 2026, the 37% bracket starts at $640,600 for singles but only $768,701 for married filing jointly, so nowhere near double.

Source: CNBC

Second, there’s the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). If your modified adjusted gross income exceeds $200,000 for singles or $250,000 for married filing jointly, you’ll pay an additional 3.8% tax on investment income, including capital gains and dividends from taxable accounts (though this doesn’t apply to qualified retirement account distributions).

For a physician couple with $400,000 in combined income, NIIT adds real cost to taxable account returns. For instance, if you’re generating $20,000 annually in qualified dividends, you’ll pay regular capital gains tax (likely 15%) plus 3.8% NIIT for an effective 18.8% rate.

This tips the scales slightly toward backdoor Roth contributions, though the limited contribution space means you’ll still need taxable accounts for any serious wealth building.

The Financial Advisor Consensus

The experts say you gotta do both. And they’re right. Why does it have to be apples or oranges when a good fruit salad has both?

CFPs consistently recommend a specific priority order for high-earning physicians that firstly calls for you to max out your 401(k)/403(b) to get that $24,500 (or $32,500 if 50+) tax-deferred, especially if there’s an employer match.

Second, fund backdoor Roth IRAs at $7,500 per person ($8,600 if 50+) for you and your spouse before, third, maxing out your HSA if you have a high-deductible health plan at $4,400 for singles or $8,750 for families in 2026 (this is the most tax-advantaged account available).

Fourth, explore the mega backdoor Roth if available, since some 401(k)s allow after-tax contributions up to the $72,000 total contribution limit in 2026.

And finally, everything else goes to taxable accounts where you should invest in tax-efficient index funds and use tax-loss harvesting.

Don’t Overthink It, Doc

At the end of the day, having to choose between backdoor Roth contributions or taxable investing is a “rich person problem” but it’s a good problem to have. You’re in a position where you’re saving more than the government allows in tax-advantaged space. That’s winning.

The backdoor Roth is a layup. Do it. Every year. For both you and your spouse. It’s $15,000–$17,200 annually of tax-free growth you’d otherwise miss out on.

But don’t stop there. Your taxable account is where you’ll build real wealth. The kind that lets you retire early, pivot careers and build generational wealth. It’s more flexible, scales infinitely, and the tax treatment isn’t as bad as most people think.

As one seasoned investor on Bogleheads put it, “We have a couple million in taxable VTSAX, and gladly pay the taxes on the dividends. One of the best problems in my life. I am striving for it to worsen.”

That’s the mindset. Not “how do I avoid all taxes” but “how do I build wealth efficiently while managing taxes intelligently.”

Do both. Be strategic about asset allocation. Don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog. And remember, paying taxes means you’re making money.

Also read: Why Do High Earners Struggle to Feel Rich

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is a backdoor Roth IRA and why do I need it?

A backdoor Roth IRA is a two-step process that allows high earners who exceed income limits to still contribute to a Roth IRA. You make a non-deductible contribution to a traditional IRA, then immediately convert it to a Roth IRA. For 2026, if you’re making over $168,000 (single) or $252,000 (married filing jointly), this is your only path to Roth IRA contributions. Check out our step-by-step Vanguard backdoor Roth tutorial or review the comprehensive backdoor Roth FAQ for answers to common questions.

I have an old rollover IRA with $100,000 in it. Can I still do the backdoor Roth?

Technically yes, but the pro rata rule will make it painful. With $100,000 in pre-tax IRA money, roughly 93% of your $7,500 backdoor conversion would be taxable, defeating the purpose. Your best option is to roll that IRA money into your current employer’s 401(k) plan before attempting the backdoor Roth. Most 401(k) plans accept incoming rollovers — check with your plan administrator.

Should I max out my 401(k) before doing a backdoor Roth?

Absolutely. The priority order for high-earning physicians is: (1) Max your 401(k)/403(b) (that’s $24,500 in 2026 or $32,500 if 50+), (2) Fund backdoor Roth IRAs for you and your spouse, (3) Max your HSA if you have a high-deductible health plan, (4) Explore the mega backdoor Roth if available, and (5) Invest everything else in taxable accounts.

Is a taxable brokerage account really worth it compared to more retirement accounts?

For high earners, taxable accounts are essential once you’ve maxed tax-advantaged space. They offer flexibility, no RMDs, step-up in basis for heirs, and better tax treatment than most people realize. Plus, if you’re planning early retirement, you’ll need accessible funds before 59½. Read why taxable accounts are crucial for early retirees and how taxable accounts can actually be better than Roth IRAs in certain scenarios.

What investments should I hold in my taxable account vs my Roth IRA?

Put high-growth, potentially volatile assets in your Roth where tax-free growth matters most. Keep tax-efficient broad-market index funds (VTI, VTSAX) in taxable accounts. Save tax-inefficient investments like bonds and REITs for your 401(k) or traditional IRA.

What is tax-loss harvesting and should I be doing it?

Tax-loss harvesting involves selling investments at a loss to offset capital gains and up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually. For high earners in the 35–37% tax bracket, this can save $1,000–$1,400 per year. Unused losses carry forward indefinitely. It only works in taxable accounts. Check out our comprehensive guides on tax-loss harvesting with Vanguard and Fidelity, plus top 5 tax-loss harvesting tips.

I’m married and we both work. Should we each do a backdoor Roth?

Yes. IRAs are individual accounts, so you and your spouse can each contribute $7,500 (or $8,600 if 50+) annually. That’s $15,000–$17,200 per year of tax-free growth you’d otherwise miss. Even if your spouse doesn’t work, they can still do a spousal backdoor Roth as long as you have sufficient household earned income.

What’s the deal with the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)?

If your modified adjusted gross income exceeds $250,000 (married filing jointly) or $200,000 (single), you’ll pay an additional 3.8% tax on investment income from taxable accounts, including dividends and capital gains. This doesn’t apply to qualified retirement account distributions. For a physician couple earning $400,000, NIIT adds real cost to taxable account returns, which slightly favors maxing out Roth contributions first — but you’ll still need taxable accounts for serious wealth building.

Can I really access my taxable account money anytime without penalties?

Yes. That’s one of the biggest advantages. Unlike retirement accounts with 10% early withdrawal penalties before 59½, your taxable account is completely liquid. You’ll only pay taxes on realized gains when you sell. This makes taxable accounts perfect for early retirement, major purchases, or unexpected needs.

How do I keep my taxable account simple while staying tax-efficient?

Stick to broad-market index funds with low turnover, invest less frequently (monthly or quarterly instead of biweekly) to reduce tax lots, and use tax-loss harvesting to consolidate positions when opportunities arise. If it gets too complex, consider a roboadvisor that handles TLH automatically for 0.15–0.30% annually.

What about HSAs? Where do they fit in?

HSAs are actually the most tax-advantaged account available — triple tax benefit with pre-tax contributions, tax-free growth, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses. For 2026, you can contribute $4,400 (singles) or $8,750 (families). Max this out after your 401(k) match but potentially before maxing your entire 401(k), depending on your situation. Discover why the HSA is the ultimate retirement account.

Should I prioritize paying off my mortgage or investing in taxable accounts?

This depends on your mortgage rate, risk tolerance, and emotional relationship with debt. Paying off debt offers a guaranteed return equal to your interest rate, while stock market returns are uncertain. Many physicians do both. They make extra mortgage payments while also investing in taxable accounts. It’s a personal decision where there’s no universally “right” answer, just the right answer for your situation and peace of mind.

1 thought on “Backdoor Roth vs Taxable Investing for High Earners”

How wonderfully clear! Thank you.