We don’t usually talk about what happens in the unseen corners of aging. Not in any real detail. The daily routine of bathing, dressing, and feeding is rarely part of the financial planning spreadsheets or retirement seminars.

But sooner or later, most of us will come face-to-face with these considerations, either for our parents or for ourselves.

And when that time comes, we will hope, maybe even expect, that someone will be there to help.

In America, that “someone” is increasingly a foreign-born worker (Labor Department Report). Immigrants make up a significant portion of the workforce in long-term care settings, from home health aides and personal care assistants to the housekeepers and dietary staff who keep facilities running smoothly behind the scenes.

Table of Contents

ToggleMany of them come to this country not for opportunity alone, but to take on the kind of essential labor few others are willing to do, day after day, often for modest pay, and with little recognition.

They are the ones who stay when others don’t, who build trust with patients suffering from dementia, who learn routines, absorb habits, and quietly hold things together.

But in recent years, the flow of this labor force has slowed. Changes in immigration policy, tighter visa pathways, and the reduction of refugee admissions have all played a role in thinning the ranks of caregivers. And the final nail in the coffin? The current administration’s aggressive stance on immigration.

For long-term care facilities already stretched thin by staffing shortages and rising demand (nearly 10,000 Americans turn 65 every day), the impact has been quiet but consequential.

To be clear, the lack of noise does not mean that this is a future problem. It’s already unfolding in facilities across the country. And for families who rely on elder care, it raises a difficult but necessary question: What happens when the people we rely on are no longer available to do the work?

Don’t miss out on The First 100 Days: How Has Healthcare Fared In The New Era

The Fragile Backbone of Elder Care

Foreign-born workers are the unsung heroes of the American elder care system.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, over 41% of home health aides in 2024 were immigrants. Additionally, 22% of nursing assistants and 28% of personal care aides were foreign-born.

These are not niche numbers; they represent hundreds of thousands of workers who are caring for millions of aging Americans.

When compared to the general workforce, where immigrants make up only 19%, the severity of losing these workers starts to hit home.

Within the long-term care sector, particularly in jobs like housekeeping, food services, and direct patient care, this ratio is much higher. In housekeeping and maintenance alone, 30% of nursing home staff are foreign-born.

And they’re not easily replaced.

What Happens When a Caregiver is Deported?

This is not a hypothetical question. It’s happening now.

In June, Rachel Blumberg, CEO of Sinai Residences in Boca Raton, Florida, was forced to fire 10 employees after the White House revoked their work permits. Many had worked there for years and were beloved by residents.

“They have been part of what has made my life so secure and with quality for almost 10 years now, and it’s like how dare somebody tell them they can’t continue to help me,” said Dorothy Wizer, one of the residents.

“It kind of felt like a funeral,” Blumberg said. “One person after another. It’s hard to look somebody in the eyes and tell them, ‘You can’t work here, even though you’re amazing at your job.’”

Thirty more workers (mostly Haitian) are expected to lose their protected status by August. And Blumberg estimates it will cost an additional $600,000 per year in higher wages to attract and retain new workers, costs that will ultimately be passed on to residents.

And many facilities don’t have that option.

Medicaid Math

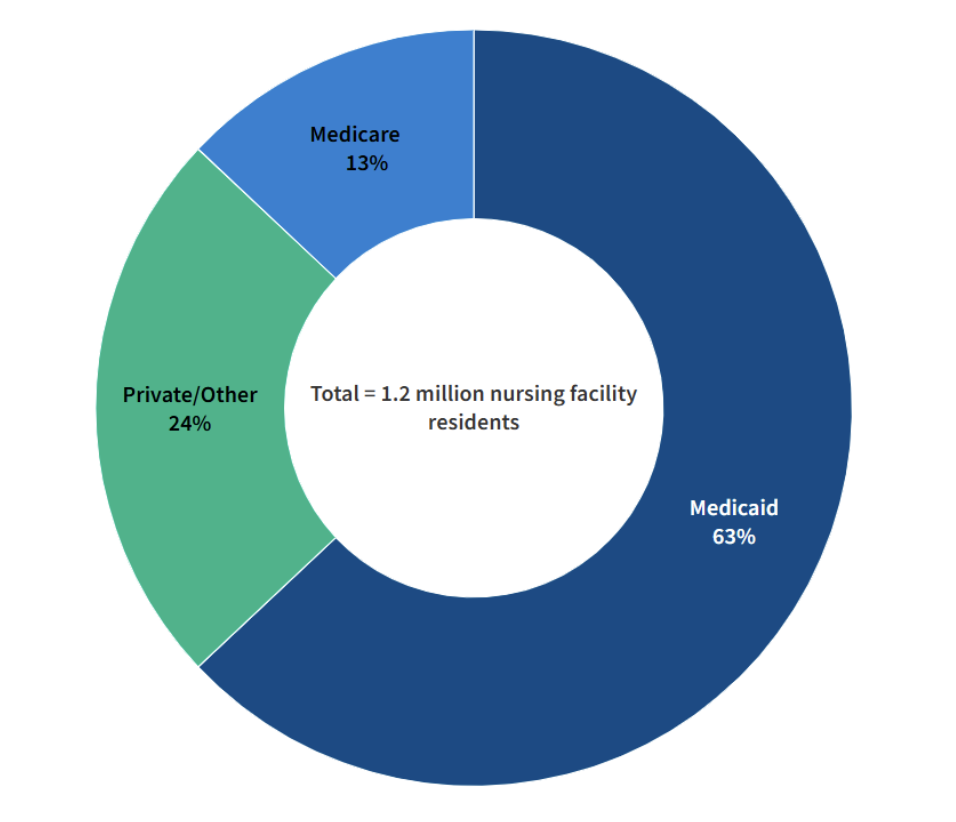

The majority of nursing home care in the U.S. is funded by Medicaid.

But Medicaid doesn’t reimburse generously, and it certainly doesn’t account for emergency wage hikes when immigrant caregivers are deported.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid covered 63% of nursing home residents in 2024.

Image Source: KFF

Facilities operating on such tight margins can’t compete with hospitals or private duty agencies in pay.

That’s why many turned to immigrant workers in the first place, as they were willing to take lower wages for hard, often thankless work. These caregivers aren’t taking jobs Americans want. They’re taking jobs Americans won’t take.

Is the Quality of Care at Risk?

Yes. And there’s data to prove it. According to a study published in Health Affairs, a higher rate of turnover in nursing home staff results in a loss of quality of care.

Not to mention that according to research (PDF) carried out by the University of Connecticut, facilities with higher proportions of immigrant workers had better care quality, particularly on measures like infection control, hospital readmissions, and patient satisfaction.

These findings run counter to a common anti-immigration trope: that immigrants lower labor standards. In elder care, the opposite appears to be true.

David Grabowski, a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, noted that regions with more immigrant labor during the COVID-19 pandemic fared better in maintaining staff levels and preventing outbreaks.

“A lot of people say foreign-born workers crowd out jobs or reduce care quality. That’s not the case here,” he said.

The Quiet Shockwaves of a Policy Earthquake

The Trump administration’s restrictions on refugee resettlement, asylum programs, and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) have compounded what was already a fragile system.

The Biden administration, while reversing some policies, had not reinstated broad protections for many affected groups, particularly Haitians and Central Americans who make up a large portion of the caregiving workforce.

According to the American Immigration Council, as of 2024, nearly 1.1 million immigrants lived and worked in the U.S. under TPS. Many of whom worked in healthcare-adjacent roles.

As legal uncertainties loom, employers are now hesitant to invest in training or hiring immigrants with unstable status.

Meanwhile, new visa pathways for low-wage healthcare workers are virtually nonexistent. The U.S. immigration system favors high-skill, high-wage labor like tech engineers, not certified nursing assistants.

Read about How The Big, Beautiful Bill Is Going After Foreign Investors

The Long Shadow of COVID-19

During the pandemic, we witnessed a staggering exodus, with nursing homes losing nearly 250,000 workers — more than any other healthcare sector. As of mid-2024, the sector had only regained half of those jobs.

The American Health Care Association (AHCA) reports that since 2020, at least 774 nursing homes have closed, displacing 28,421 residents. The main driver? Staffing shortages.

Image Source: AHCA (PDF)

The Biden administration’s proposed staffing mandates, though well-intentioned, ended up pushing struggling facilities further toward collapse since immigration-based labor solutions were never implemented, and funding was never part of the equation.

Who Will Do the Work?

Critics of immigration argue that unemployed Americans could step in. The White House has pointed to data showing that 9.8% of people aged 16–24 remain unemployed.

“There is no shortage of American minds and hands to grow our labor force, and President Trump’s agenda to modernize our workforce represents this Administration’s commitment to capitalizing on that untapped potential while delivering on our mandate to enforce our immigration laws,” said White House spokesman Kush Desai.

But these young workers aren’t flocking to caregiving jobs. Turnover in elder care is already astronomical. Annual turnover for CNAs (certified nursing assistants) exceeds 41%, and for home health aides, it can reach 82%.

This isn’t a problem of supply. It’s a problem of will, training, and sustainability.

You can’t just drop anyone into a memory care ward and expect them to hit the ground running. These jobs are taxing, both physically and emotionally. And it’s America’s aging population that bears the brunt of staffing shortages and policies that add fuel to the fire.

Behind every policy decision, there’s a human story.

There’s the autistic man in Virginia whose caregiver was deported for a minor crime committed years ago. According to the New York Times, that patient is now struggling emotionally, having lost the only professional who understood how to help him get through rough times.

There’s the caregiver, “Alex”, who lost his livelihood, his freedom, and any chance of making his American dream come true.

Then there’s the resident, who might be your grandmother, perhaps. She now has to wait twice as long for help with toileting because the hall is short-staffed, again.

We spend our lives caught up in the rat race or enjoying every moment of agency and control. Yet as we near the end of that journey, we hope there will be someone there with us in our final years. Someone patient, gentle, and skilled.

Someone who speaks softly as they help us out of bed. Someone who won’t mind the diapers or the repetition or the sadness of watching time pass through cloudy eyes.

That someone is increasingly an immigrant.

And they are leaving.

Not because they want to, but because we are making them.

There is no national plan for who will replace them. No legion of young Americans lining up to do the work. Only silence, empty wings, and residents left waiting in wheelchairs.

If we cannot summon the will to protect the people who care for our most vulnerable, then we must ask ourselves what kind of nation we are becoming, and who will be left to care for us when it’s our turn.

Don’t forget to read about MAHA: Breaking Down the Latest Healthcare Mandate

FAQs

Q: Why are immigrants overrepresented in elder care?

A: Many immigrants are drawn to elder care jobs because they are accessible without advanced degrees, offer steady employment, and fulfill a cultural or religious value around caring for elders. U.S.-born workers often avoid these roles due to low wages and high physical/emotional demands.

Q: Can’t nursing homes simply raise pay to attract American workers?

A: Not easily. Most nursing homes rely on Medicaid, which reimburses at low rates. Without government funding increases, they can’t afford to raise wages meaningfully.

Q: What about robot caregivers or tech solutions?

A: While technology is advancing, human touch remains irreplaceable in elder care, especially for dementia patients, those with complex emotional needs, and palliative care scenarios.

Q: Has Congress proposed immigration reform specific to elder care?

A: Some lawmakers have floated visa programs for healthcare aides, but none have passed. The focus remains on high-skill visa pathways like H-1B.

Q: What countries are most foreign-born caregivers from?

A: The top countries include the Philippines, Mexico, India, Jamaica, Nigeria, Haiti, China and the Dominican Republic..

Q: Is there a legal way to bring in foreign caregivers?

A: Not directly. The U.S. immigration system has limited pathways for low-wage caregiving roles. Most enter through refugee programs, TPS, family reunification, or are undocumented.